Tadeusz Makiewicz

During the first centuries ad, referred to by Polish archaeologists as the Period of Roman Influences, three large cultural complexes, probably associated with three different peoples, made their mark in the present-day territories of Poland. Southern and central Poland was occupied by the Przeworsk Culture, which gained its name from the village of Przeworsk, situated in Lesser Poland (Maűopolska), where the first cemeteries typical of this culture were discovered. This culture emerged at the beginning of the second century bc and continued to thrive for several hundred years, right up until the Migration Period. The regions of Warmia and Mazuria (Mazury) were inhabited by representatives of the Western Balt Culture, which developed independently of its neighbours, and differed from them distinctly, bearing, however, a clear relationship to Baltic peoples. In contrast, during the first decades ad, an entirely new culture began to take shape in Pomerania. Archaeologists dubbed it the Wielbark Culture, after the site at Wielbark (currently Malbork-Wielbark), where the first cemetery of this culture was found. This area of Poland had previously been occupied by the Oksywie Culture, closely related to the Przeworsk Culture, but differing in many aspects from the subsequent Wielbark Culture. At the beginning of its existence the Wielbark Culture had exactly the same territorial extent as the Oksywie Culture. Thus, it covered an area stretching along the Lower Vistula from Gdańsk to Chełmno in the south, whilst to the west it encompassed a large proportion of Pomerania, reaching beyond the River Parsęta. Later on it extended even further, into the of Kashubian and Krajeński Lakelands and into northern Greater Poland, stretching south towards the Poznań region. Another marked change took place during the first half of the third century ad, when the Wielbark Culture withdrew from Greater Poland and from virtually the whole of Pomerania, apart from those territories situated nearest the Vistula Estuary. At the same time, expansion to the south-east began, Wielbark communities settling in Mazovia (Mazowsze) and Little Poland to the east of the Vistula, even reaching as far as the Ukraine.

Hence, by about the mid first century ad, the Przeworsk societies which had previously lived in northern Greater Poland had been displaced by the Wielbark Culture whose own freshly founded settlements and cemeteries continued to exist here for approximately 150 years. These cultures were separated by a clear divide, contacts between them having been so minimal as to not be detectable by archaeological methods. Thus, we can conclude that they represented two clearly disassociated tribal groups.

What were the distinguishing characteristics of the Wielbark Culture? Wielbark societies practised both cremation and inhumation rites for burying their dead. The proportion of inhumation to cremation burials at Wielbark Culture cemeteries varies greatly from site to site. It is difficult to say where these differences in burial rites came from; whether they resulted from differences in religion or from the different cultural traditions of a particular family. This latter theory seems rather more convincing, as identical grave goods accompanied both forms of burial.

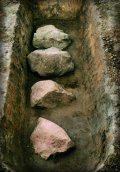

The custom of raising stone-covered burial mounds of various shapes is another typical feature of this culture, as are stone circles, stelae and numerous types of cobble cladding. Wielbark Culture grave goods did not include weapons or tools (which was one of the stock items of Przeworsk Culture burials), ornaments and elements of costume taking precedence in this respect. A very limited number of male burials contained spurs - the only object in the entire grave assemblage related to a warrior’s equipment. The final characteristic feature of this culture is the predominant use of bronze for making ornaments and dress accessories, silver being used much less often and gold only very rarely, whilst iron was practically never used. It should also be added that virtually no Wielbark settlements have been recorded in this area, which means that we have a rather one-sided view of this culture as we know very little of the everyday life of its communities.

Evidence of the Wielbark Culture in Greater Poland comes from the cemetery at Kowalewko. Two large Wielbark cemetery sites had already earlier been excavated in northern Greater Poland (at Lutomie and Słopanów), whilst numerous smaller burial grounds and single graves, or individual items from them, had also been noted across the entire region. The cemetery at Kowalewko is, however, one of the largest burial sites in the whole of Poland and has yielded a particularly rich collection of beautiful finds. Archaeologists had not previously been aware of its existence. Therefore, it is entirely thanks to the fact that the gas pipeline was scheduled to pass through the cemetery that led to its discovery and excavation.

The Kowalewko cemetery site was first recorded during the course of fieldwalking along the route of the proposed gas pipeline. Excavation work began in 1995 and to-date has revealed a total of over 400 graves. By looking at a site plan showing all of the burials discovered thus far and taking into consideration the surrounding terrain, we can estimate that approximately 80% of the whole cemetery has now been explored, meaning that the grand total of burials may ultimately amount to between 500 and 550.

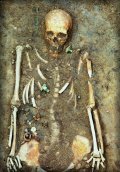

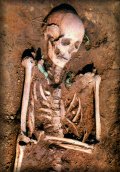

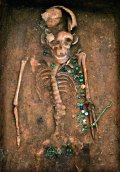

Both cremations and inhumations are represented at this cemetery. The latter are, naturally, of smaller dimensions, the burnt bones of the dead having been placed inside a pottery vessel known as an urn or deposited directly inside a modestly-sized burial pit. Cremations make up approximately 40% of the burials at Kowalewko. Inhumations were placed in plank-built coffins, or very occasionally, inside a coffin made from a single hollowed-out tree-trunk. Some graves were marked on the surface by a solitary stone, whilst in two instances, large boulders, selected for their specific form and additionally hewn into shape, had been used. Strange, atypical rituals involving the treatment of the skeleton were observed in a number of burials, such as turning the skull upside-down or positioning it on the chest or in the leg area.

No differences were noted in the grave goods included with inhumation and cremation burials.

The deceased individual was interred with articles which had belonged to him or her in life. In accordance with the principles of this culture, these consisted almost exclusively of dress accessories or ornaments, i.e. bracelets, bead necklaces, pendants, buckles and bronze belt fittings. The most numerously encountered form of burial good consisted of fibulae (a type of brooch used for fastening robes), which were often very decorative and extremely well-made. Two or three of these were usually found accompanying each burial. Fewer graves contained only a single fibula, whilst some rare examples had up to four. The fibulae are found in pairs, positioned at shoulder height, with the third brooch securing the robe at the chest. Bracelets, often with finials in the shape of stylized snake’s heads, also served as grave goods. Hair-pins made of silver, bronze and bone were another common find. Beads, however, accounted for the greatest quantity of burial finds. They came in various shapes and sizes and were made from amber, glass or silver. In some cases, necklaces consisting of up to 300 beads were found. These necklaces were fastened with silver ‘S’-shaped clasps, made of either silver or gold and very skilfully decorated. Further items of jewellery included bronze and silver pendants and, in a very few rare instances, gold ones. Pottery vessels, bone combs and metal fittings from wooden trinket boxes also featured as grave goods, whilst bronze spurs were found exclusively with male burials. Spurs were the only warrior-related items found in these graves. They included examples made in the Roman Empire and imported to this region. Undoubtedly, the most attractive artefact among the vast array recovered was a beautifully decorated bronze jug.

The Kowalewko cemetery dates from approximately the mid first century ad, to c. ad 220. Thus, it remained in use for a period of about 170 years - a total of about seven generations. We can conclude, therefore, that one generation numbered around eighty individuals.

It is worth adding that a Wielbark Culture settlement site had already earlier been excavated at Kowalewko; Greater Poland being the only region where numerous other settlements of this culture have been discovered. Several of these sites were recorded during the course of archaeological fieldwork along the route of the pipeline. As a result, we have been able to gain an insight into the settlement types and everyday lives of Wielbark societies.

The outline given above of the cemetery site at Kowalewko and of the Wielbark Culture to which it belongs does not answer the question of which race of people this culture was related to. What lies behind the strange names afforded these communities by archaeologists? Who were the people who inhabited these territories? What language did they speak and where did they come from?

Putting an ethnic origin to the many archaeologically defined ‘cultures’ is one of the most difficult problems facing researchers in this discipline today. This difficulty arises from two main sources. Firstly, what relation do archaeological cultures bear to specific ethnic units, i.e. to tribes and peoples? This issue has been hotly debated since the very dawn of archaeology and remains unresolved. Secondly, only a fragmented and very limited number of written sources exist which allude to Poland during this period, and can offer us some clues as to the nature of settlement in these territories.

Researchers have traditionally associated the Wielbark Culture with the Scandinavian peoples known as the Goths, maintaining that it was founded as a result of Gothic migration from their home territories in the Swedish province of Gotland or the Island of Gotlandia. Having completed a lengthy stay in Poland, these tribes then continued their migration to the Black Sea coast. The latest results of work carried out by archaeologists and historians indicates, however, that the real situation was not quite so straightforward and that we cannot simply equate the Wielbark Culture with the Goths.

Ancient writers, such as Pliny the Elder, Tacit and Ptolemy make mention of the Goths in their works, Tacit referring to their having been involved in an incident which took place in ad 19 on the territory of what is now the Czech Republic. The most important information, however, is proffered by the sixth-century writer Jordanes, who lived during the reign of the Emperor Justinian. Jordanes records that in the reign of King Berig, the Goths set sail from the Island of Skandia (i.e. modern-day Scandinavia) in three ships, alighting at the other side of the ocean, in a land which they called Gothiskandza, subjugating the neighbouring populations. Under the reign of Berig V they embarked on a further voyage to the land of Oium, i.e. to the northern territories of the Black Sea coast. A variety of interpretations have been put forward in relation to the three ships. The number was considered by some to have been merely symbolic, whilst others believed that it stood for three tribes - the Ostrogoths, Visigoths and Gepidae - or took it literally to refer to three sailing vessels carrying the Amal royal family, of which Theoderic the Great was a descendant.

Recent archaeological research and lengthy debate on this subject have, however, established that the Wielbark Culture did not simply come into being as a result of the arrival of tribes of Scandinavian Goths in Pomerania. Instead, it evolved from the development of the local Oksywie Culture, possibly having been subject to outside influences from Scvandinavia. This is evidenced primarily by the fact that in its initial phase, the Wielbark Culture had exactly the same territorial extent as the Oksywie Culture, many cemeteries having been kept in continued use by these two societies. Wielbark communities comprised mostly members of tribes already settled in this area with the addition of Scandinavian migrants, who maybe arrived here in small groups. At present, it is thought that those areas which were inhabited directly by Gothic peoples are characterised by the presence of extensive barrow cemeteries of the Odry-Węsiory-Grzybnica type, at which stone circles consisting of large boulders were raised. These were sites of a ritual character where tribal meetings (known as things) took place. Sites of this type are found in the Kashubian and Krajeński Lakelands, extending to the Koszalin region in the Central Lakelands, hence, to the west of the Vistula. These burial grounds began to appear across this area during the latter part of the first century ad, at the same time that the Kowalewko cemetery was founded.

This area is also associated with the Wielbark Culture, whose communities settled in Greater Poland during the same period and exhibit a number of close links with the aforementioned lakelands. We do not, however, have any evidence of stone circles or cobble-clad graves from Greater Poland, barrow burials being a rarity - only three having been recorded in the peripheral zone of this region. The Wielbark Culture appears to have been composed of Scandinavian Goths and Gepidae as well as of earlier local communities - the Venedi and Rugii. The woodlands of the Kashubian and Krajeński Lakelands, lying to the north-east of Greater Poland, are where groups of Goths are believed to have established their own settlements. The Wielbark Culture is thought to have reached Greater Poland from Pomerania, displacing the local Przeworsk Culture. Whether the Wielbark Culture was really of Gothic ethnic origin or made up of a number of different tribes (including Goths), we cannot say. In later years, at the beginning of the third century ad, they abandoned the territories of Greater Poland and Pomerania, moving on, together with their kinsfolk, until they reached the promised land of Oium, situated in modern-day Ukraine, where they founded their mighty empire.

BACK