Janusz Czebreszuk

The transition between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age was one of the greatest turning points in European history. One of the most noticeable features of this period was the increasing importance of herding and rearing domesticated animals. The origins of several institutions fundamental to European civilization can be traced back to this episode of prehistory.

Very little was previously known about the archaeological record of this period in the areas transected by the Polish section of the international gas pipeline. Remarkably little material dating from this era had been noted in these regions, especially when compared to the numbers of finds discovered from both the preceding and the following phases of prehistory (i.e. the Early Neolithic and the Lusatian Culture). It was hoped that the gas pipeline development, by presenting archaeologists with an opportunity to examine a gigantic W-E trial trench cutting across the whole of Poland, might help change the existing picture of life in the third millennium bc. Even now, before the final reports have been written up on all the archaeological materials recovered, we can safely say that these hopes have not ended in disillusion. Archaeological investigations along the route of the gas pipeline have yielded many unique discoveries dating from the final phase of the Neolithic period and the beginnings of the Bronze Age.

Crop cultivation was fundamental to the way of life of the early agrarian farming communities living in Central Europe during the third millennium bc. However, other contemporary societies also emerged who relied on a totally different strategy of food procurement. The majority of groups inhabiting the European Lowlands began at this time to place greater emphasis on the rearing of domesticated animals as the basis of their livelihoods. Moreover, the beginning of the third millennium bc, marks the first appearance in this part of Europe of peoples whose way of life approaches that described in classical ethnology as pastoralism. In archaeological terms, these societies are referred to as belonging to the Corded Ware Culture.

For archaeologists dealing with the transition between the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age, one of its most distinctive characteristics is the wide variety of cultural groups encountered during this period. These societies often coexisted within a relatively small area Thus, in the region of Kuiavia, for example, the number of known contemporary archaeological cultures included the Funnel Beaker Culture, the Globular Amphorae Culture, and the Corded Ware Culture. Another noticeable phenomenon was the increasingly frequent appearance of new taxonomic units, clearly reflected in the changing attributes of ceramic assemblages. This indicates that, in comparison to the earlier phases of the Neolithic, cultural mutations in the period under discussion took place more swiftly. Excavations along the line of the international gas pipeline fully confirmed this complex sociological picture of life at the end of the Neolithic and the onset of the Bronze Age.

Abandoning the stable lifestyle of agrarian farming communities in favour of pastoralism left relatively few traces of settlement in the archaeological record. In contrast, the proportion of burials recorded during excavation is considerably greater. Animal husbandry, and in particular pastoralism, involves a far more nomadic way of life. In consequence, settlements raised by such societies were usually smaller and of a more temporary nature, consisting of light-weight constructions, often in the form of shelters. As they made such a negligible impression on the landscape, identifying pastoralist settlements has always been fraught with methodological difficulties for the archaeologist. Excavations carried out during the course of the international gas pipeline project, which cut a random section from west to east across Poland, led to the discovery of a number of new settlement complexes. These included site 31/32 (341) at ¯abno and site 1 (79/80) at Sieniarzewo. Although these sites may not be particularly spectacular to look at, they are extremely rare and valuable in research terms, as they allow us to gain a fundamental insight into the characteristics of pastoralist settlements dating from the third millennium bc.

The most substantial core of evidence relating to the Neolithic/Bronze Age transition undoubtedly comes from burials. Archaeological work preceding the laying of the gas pipeline brought to light graves from every phase of development of the societies of this period. Particularly noteworthy were the earliest forms of burial: barrows surrounded by a ring-ditch, in which, originally, a palisade would have stood, marking the height of the mound. In terms of religious beliefs this palisade would have delimited the extent of the sacred area (sacrum), the mortuary chamber - usually containing a single skeleton - being located in its centre, below the barrow mound. This type of grave is reminiscent of those known from pastoralist communities in south-east Europe. Only one other burial of this kind had previously been noted in northern Poland. The gas pipeline project led to three new discoveries of palisaded barrows. One of these was recorded at the Kuczkowo 5 site. Details of its construction, in the form of a ditch (Photo. ) and a series of post-holes (Photo. )***, were particularly well-preserved. None of the mounds of the tombs in question had survived, having been destroyed by ploughing over the years. This points to one of the major difficulties in discovering barrow-burials in the part of Poland through which the transeuropean gas pipeline runs: Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) and Kuiavia belong to those areas of the country which have been subjected to the heaviest human interference. Only open-plan and linear excavations, such as the gas pipeline venture, offer any hope of discovering this type of burial monument.

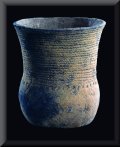

Early Bronze Age graves in northern Poland exhibit different cultural influences, this time coming from the north-west, hence form Jutland and northern Germany, instead of the south-east. Burials dating to this period are no longer covered by a mound. The construction of the grave itself also features elements commonly encountered in the north-west. One such characteristic is the lining of the burial chamber with stones. This type of mortuary structure is referred to by archaeologists as a cist grave - an example of which was found at site 1 in Kowalewko (Photo. ). Influences from the north-west are further evidenced by grave goods in the form of distinctly shaped and decorated pottery vessels, an example of which was recovered from site 1 at Siniarzewo (Photo.).

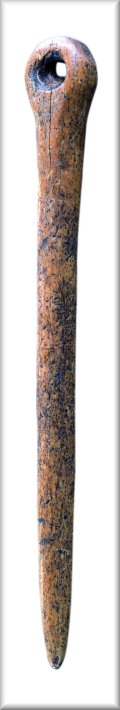

The youngest grave goods, such as those discovered at site 5 in Kuczkowo (Photo. ), are related to a new set of cultural traditions, signalling the beginning of contacts with the south. The features of these burial assemblages point to links with the earliest Bronze Age cultures of the Carpathian Basin.

To what extent did the attributes and innovations of the Neolithic/Bronze Age transition period, so clearly perceptible in the archaeological record, reflect the nature of contemporary society?

We have already mentioned that communities of the third millennium bc were more mobile than their predecessors. This mobility, however, was only spatial (geographic) and applied to settlement patterns (temporary camps). More fundamental than this was the accelerated rate at which changes in the structure of society took place. It was during the transition from the Neolithic period to the Bronze Age that the process of perceiving people as individuals, independent of their group identity, began. The agrarian model of life followed by earlier Neolithic communities was founded on the concept of an egalitarian society. In making the change to animal husbandry and pastoralism, the individual became of greater importance, playing an active role as one of the participants in a social process, rather than doing whatever task was allotted by the group to which he or she belonged. These changes are particularly noticeable in the burial rituals of the time. All of the graves dating from this period discovered during the course of the gas pipeline excavations consisted of single-grave burials. No multiple burials, which are common among egalitarian societies, were noted. It is worth underlining at this juncture that giving recognition to the individual was a basic requirement in developing concepts such as personal freedom and open competition, which are fundamental to European civilization.

Much can also be learned of contemporary societies from the grave goods which they buried with their dead. These deposits adhered to a strictly defined canon: one ceremonial pottery vessel (usually a carefully made and richly decorated fine ware beaker) and weapons consisting of archery equipment (of which only the flint arrowheads survive to this day) and a stone axe or flint dagger.

The presence of ceremonial drinking vessels, such as the beaker from site 1 at Kowaleko (Photo. ) or the previously mentioned vessel from Siniarzewo (Photo. ) witnesses the origins of fraternities (associations or secret societies?) whose group rituals involved the consumption of intoxicating beverages (alcohol). It is in these libations, which were either of a cult character or designed for social bonding, that we should seek the origins of the ancient Greek sympósion and the ‘round-table societies’, so highly prized among modern-day European cultures.

For their part, the rich weapon assemblages evidence the appearance of another significant feature of European history - namely, war, or, to be more precise, the art of warfare. The origins of the latter are deeply rooted in this particular episode of prehistory. The majority of graves dating from this period, including those discovered along the route of the gas pipeline, consisted of warrior burials. It is among these warriors that what is known in European civilizations as the ethos of chivalry or the morality of ‘men of war’ took shape.

As has already been emphasised several times, the transition period from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age marks a stage in the history of Europe which laid the foundations of numerous traits specific to our civilization. The recognition of the individual, the development of increasingly more complex social structures (in the form of fraternities or associations), the beginnings of warfare and the ethos of chivalry are but a few aspects of the legacy inherited by modern-day societies from the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age period.

Until recently, we had only a very cursory idea of the role played in these intricate processes of socio-economic change by the Polish Lowlands communities of the third millennium bc. Excavations along the transeuropean gas pipeline have provided a wealth of new archaeological materials which have considerably broadened our existing knowledge of this period. As a result, even now, before all the final reports and analyses have been drafted, we can see that all of the crucial cultural changes which took place throughout Europe at the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age are reflected in the archaeological record left behind by the populations inhabiting the Polish Lowlands at this time. Although these territories did not constitute the cultural centre of Europe, the well-developed network of routes traversing them meant that new ideas found their way here very quickly, both from the south and the west - thus, from the most culturally significant areas of third-millennium-bc Europe.

BACK