|

Jarmila Kaczmarek,

Andrzej Prinke

(Poznań Archaeological Museum)

Archaeology misused:

Polish-German dialogue in Greater Poland

in the period of developing

nationalisms (1920-1956)

|

In

the Polish language there are a few words related to the concept

of nation that are similar in form but different in meaning. These

words are as follows: "naród" - nation, "narodowość" - nationality,

"nacja" - old-fashioned for nation and "nacjonalizm" - nationalism.

Naród is a separated ethnic community that is often organized

in a state; naród is actually identical with the old Polish nacja

of a Latin origin. The related narodowość is also a separated

ethnic community, it does not however need to be a sovereign state.

Love towards one's own country, towards the big state but also

towards the small local fatherland is called patriotyzm - patriotism.

The word nacjonalizm - nationalism has already a pejorative meaning

and is understood as a degenerated form of patriotism. We refer

to nationalism when an exceptional attention is paid to the nationality,

superiority of a nation's interest is indicated over the interest

of an individual or any other social group. Chauvinism is an extreme

form of nationalism in which uncritical admiration of one's own

nation is accompanied by a conviction of its superiority over

any other nations and by hostility towards them (Nowa Encyklopedia

Powszechna PWN 1996, p. 201).

Elaborating on nationalism,

that is on deformed patriotism, is extremely challenging, as it

is often impossible to spot the borderline separating cases where

it is still permissible to speak about the fight for just rights

from cases where speaking about just rights has already chauvinistic

grounds. Separating patriotism from nationalism is especially

difficult in instances when an ethnic group is incorporated into

a foreign state against its will, it is oppressed by that state,

sometimes even exterminated, and the property of this ethnic group's

members are transferred to members of some other ethnic group

without any observance of their rights. How long are people allowed

to feel hurt and miss after or for their Promised Land? What should

be done if an ethnic group settles in a cradle of some state,

grows bigger and stronger and after some time starts to demand

e.g. sovereignty for themselves? These are issues that have not

been answered so far. |

| 1. Political conditioning

|

| 1.1. Greater Poland under the rule of the

King of Prussia |

fig. 1 |

In

order to understand the merits of the Polish-German conflict in

years 1920-1956, one will need to go slightly back in time. In

the end of the 18 th century Poland was partitioned by three neighboring

countries. Greater Poland (or: Wielkopolska) became a part of

Prussia ( fig. 1). From that moment on

Poles became a national minority in the Prussian state, being

subject to increasing discrimination and trials of denationalization.

It is Germans that were privileged in Greater Poland,

supported in the 19 th century by the |

| Prussian state by means of financial subsidies

and developing education system, building temples, rendering offices

available, creating chances of promotion in the army. The group

of Germans was soon joined by the Greater Poland's Jews, who quickly

surrendered to Germanization. The Poles from the Prussian partition

were left alone in coping with this difficult situation, and so

they handled the matters of economics and social life, but also

organized secret lessons of writing and reading in the mother

tongue (from year 1901). Because it was a nationality and not

an individual social group that was oppressed, the Poles consolidated,

and the up till then poorly developed national consciousness of

the Polish peasantry found its firm grounds.

On the turn of the 19th

century according to Greater Poles, a decent Pole was someone

who felt Polish, did not surrender himself nor his family to Germanization,

had a job and worked in an honest manner, remained sober and economical,

purchased goods mainly from other Poles and thus supported the

home economics, was a Catholic tied closely to his family and

participated actively in Polish social organizations. Such an

understanding was accompanied by ill-will towards Germans and

Jews who were perceived as oppressors, which was not unjustified,

but certainly not in all cases.

On the other hand there

was an ideal German living in Wielkopolska Province that was seen

by German authorities as a Prussian subject who supported policies

of the authorities, was a Protestant (possibly of Jewish faith),

down to earth, surpassing Poles in terms of behavior and education

as well as managerial abilities, a person actively engaged in

Germanizing the country, participating in German organizations

and avoiding any closer relations with Poles. Naturally, both

representations were often only wishful thinking that had little

in common with the reality.

By the mid-eighties

of the 19th century ancient artifacts were generally considered

to be traces from the Polish past - in the sense of today's cultural

heritage of a given country. When in 1885 Bismarck, the Prussian

chancellor commissioned a supervisor of the Bydgoszcz province

to draw up a plan for accelerated Germanization of Greater Poland,

the later, apart from setting up the Colonization Commission,

pointed to the German inhabitants feeling strange. In reaction

to this statement antiquity historians and archaeologists "Germanized"

the province's past, convincing Germans into believing that their

ancestors had inhabited the territory for ages. They referred

to written sources, particularly by ancient authors, especially

Tacitus, Jordanes and Plinius. Interpretations of vague data provided

by Tacitus as alleged evidence of German ancestors being settled

in Greater Poland met with protests of local Poles, too weak however

to be convincing - there were no professional prehistorians in

the region. |

| 1.2. Polish case during the World War One |

For

Europe, and particularly its central, eastern and partly southern

parts, World War I caused by Austio-Hungary supported by Prussia,

Bulgaria and Turkey (the central powers) brought by significant

political changes. Foremost the Austrio-Hungarian Empire was dissolved

and instead a number of national countries were established. Moreover

the Russian Tsardom was abolished and in its place a multinational

Bolshevik state was brought into existence. Also Poland regained

its independence. Already the outbreak of the war made the Prussian

authorities as well as the Germans living in Greater Poland gradually

change their approach towards Poles so they would not decide to

support the anti-German alliance. It was extremely crucial because

in all three partitioning armies over half a million of soldiers

were Polish. Naturally both sides of the conflict counted on Poles

participating in their armies, therefore during the war a number

of declarations were issued on establishing an independent Polish

state in the future. On November 5, 1916 the central powers called

into existence the satellite Polish Kingdom out of a part of the

Polish territory annexed by Russia. On January 22, 1917, United

States President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the right of national

sovereignty and in his address he called for erecting a "united,

independent and self-contained" Polish state. The Poles right

of sovereign country was recognized also by Russia, and it is

both by the Petrograd Council of Workmen's Delegates (March 27,

1917) and by the Temporary Government (March 30, 1917). Germans

however put their efforts so that the possible reconstruction

of Poland would not be at the cost of Prussia. In the end of 1918

in Poznań the Commission of German Unions issued the leaflet "Wohin

gehört Posen?" (Where does Poznań belong to?) that read: "The

Poznań Province is not a Polish piece of land but a country of

German culture and customs. (...) It belongs to Germany in terms

of economics and strategy." In November 1918 Ostmarkverein (Hakata)

also made an address calling for cooperation of all Germans, "so

that our old German eastern boundaries remain with the German

nation, so that the local Germans are saved from foreign governments"

(Grześ, Kozłowski, Kramski 1976, pp. 274-277, 300-301, 363). On

November 11, 1918 the truce convention was signed and Greater

Poland remained within the borders of Germany (Grześ, Kozłowski,

Kramski 1976, p. 379), however on the turn of 1918 Poles living

in Greater Poland rose up in arms and succeeded in the fight for

freedom by force of arms. |

| 1.3. Province of Greater Poland after the

World War One |

The

Versailles Treaty settled down that the bigger part of Greater

Poland was included in the Polish state. Poles, Germans and Jews

were free to choose their citizenship, and also Germans and Jews

could return without any restrictions to Germany and sell their

real estates directly or using some help from Poland. On April

30, 1919 the Polish provincial authorities in Poznań officially

assured the German inhabitants of Greater Poland about full equality

of rights, freedom of religion and beliefs, access to state offices,

freedom to maintain and develop the German language and national

culture and protection of property (Grześ, Kozłowski, Kramski

1976, pp. 418-419). These solutions were not satisfactory to anyone.

Whereas in 1919 in Poznań

was inhabited by Germans and Jews in 42% (the Jews alone constituted

app. 5,1%), in 1921 the two nationalities constituted only 5,5%

of all inhabitants (Jakóbczyk 1998, pp. 798, 944). Although the

Germans who decided to stay enjoyed liberties they had never awarded

to Poles, they lost former privileges and became citizens not

different from Poles, had to learn the despised Polish language

to be able to communicate in offices and while travelling to Berlin,

they needed passports. Therefore they called Poland a "season

country" and demanded the borders be revised according to the

state as of year 1914.

Neither the Polish habitants

of Wielkopolska Province were satisfied with the state of facts.

They dismissed the idea that vast lands settled by the Polish

majority were allowed to Germany, and this not only in Greater

Poland, but also in Upper Silesia, all the more because the liberties

awarded to Germans in Poland were not governed by the rule of

mutuality. Any movements in that respect met with minimal reaction

of the government in Warsaw. A classic example of carelessness

about the Polish interests in the West sides is a village Kalina

in the Piła region that under the Versailles Treaty was awarded

to Poland and that was sold to Germany by the government of Poland

for 50 thousand Marks (Grześ, Kozłowski, Kramski 1976, p. 425). |

| 2.1. Beginnings of the archaeological institutions

in Greater Poland |

As

of 1919 some grounds of Polish institutional archaeology were

being laid down. At that time Polish conservation services and

university departments were established and the museum management

was adjusted for changed conditions. The interwar period was however

a challenging time for the state and the society. Attempts to

merge the three parts of Poland from under the partition were

not easy. Frictions could be observed between diverse interests

and traditions, which were equally visible in the archaeology. |

In

Poznań the new order in archaeology was organized foremost by

Józef Kostrzewski ( fig. 2). He was a typical

"citizen of Greater Poland", a remarkable organizer used to creating

necessary work tools without waiting for any official ordinances

but hoping for settling the formalities later in the future. For

Józef Kostrzewski the first years after World War I were the time

of organizing and putting the prehistory in Poznań in order, and

in the science in general the time of cultural systematizing of

the Polish territories. In 1919 in Poznań there were

two museums with their archeological

|

fig. 2 |

collections: the Polish ( fig.

3), established in 1857 (in future Mielżynski Family Museum)

and the Wielkopolskie Museum (founded in 1894 as a German Provinzialmuseum,

and in 1904 renamed as Kaiser Friedrich Museum - fig.

4). The existence of two museums made sense as long as Greater

Poland was a part of Prussia. After 1919 operations were carried

out for combining the two collections which was finally achieved

in 1924 as a new autonomous Prehistoric Department of the Wielkopolskie

Museum was founded under the management of Józef Kostrzewski.

At the same time Kostrzewski was one of the Poznań University

founders, where starting of 1919 he took over the prehistoric

department. Also the post of the prehistoric monuments conservator

was established this year held in Greater Poland during the entire

interwar period by Zygmunt Zakrzewski. Moreover in 1920 in Poznań

Kostrzewski called the Polish Prehistoric Society into existence. |

fig. 3 |

fig. 4 |

| 2.2.1. Archaeological culture or ethnos? Two

sides of the barricade |

Józef

Kostrzewski quite quickly realized that method of identifying

culture with ethnos (applied by Gustav Kossinna when supporting

the thesis about the German origin of archeological cultures)

can equally well speak for the Slavic origin of these cultures.

Kostrzewski held in high respect all three pioneers of the method:

Pič, Kossinna and Aaberg (Kostrzewski, after 1930). Therefore

when criticizing the apparent clumsiness and incoherence of Kossinna'a

thinking, Kostrzewski applied the method to support the Pre-Slavic

origin of Lusatian culture - the theory promoted already in the

19th century by southern-Slavic and Czech antiquity historians

that was presented in Poznań already in 1886 by Klemens Koehler,

a Polish archaeologist-amateur. The first note about the possibility

of identifying the Lusatian culture with the Slavic ancestors

Kostrzewski made public in Poznań in 1914 in a publication "Greater

Poland in prehistoric times", although the same year he defended

his doctor thesis "Die ostgermanische Kultur der Spätlatenezeit",

which he then published in 1919. As the number of publications

devoted to the Preslavic theory grew, he got involved in many

more disputes with some German prehistorians, and most often with

B. v. Richthofen. Kostrzewski expressed his attitude towards the

polemics with German scientists in a leaflet from 1930 Vorgeschichtsforschung

und Politik. Eine Antwort auf die Flugschrift von Dr. Bolko Frh.

von Richthofen: Gehört Ostdeutschland zur Urheimat der Polen that

he concluded with the statement: "we Poles do not need to make

references to archaeological arguments as both the historic and

ethnographic evidence speak to our advantage too explicitly. From

the political point of view it might be indifferent to us what

nationality were the prehistoric inhabitants of Poland or Eastern

Germany at that time especially that at best these were German

of Scandinavian origin and not ancestors of Germans. However as

long as the German prehistorians will lodge claims for the Polish

territory on the grounds of archaeological research, we will be

forced to refute the attacks with scientific arms" (Kostrzewski

1970, pp. 166-171). This statement of Kostrzewski is a quite faithful

reflection of his split-approach to archaeology characteristic

to his entire heritage. When reading through his own and his co-workers'

hand-written documentation (and these are thousands of documents),

the Polish-German polemics as such does not actually appear in

there. The Lusatian culture is generally called the Lusatian culture

and very rarely the Pre-Slavic one. The letters surviving in MAP

archives written by German scientists (e.g. E. Sprockhoff, E.

Petersen, M. Jahn, La Baume, H. Jahnkuhn, G. Dorka, K. Langenheim,

P. Paulsen, E. Nickel, H. Knorr) refer to the data exchange, requests

for consultations or rendering the collections available. They

rarely mention the ethnical identification such as "burgundy culture"

in the letter by Dr. Schulz or Bohnsack from Königsberg, or a

political demonstration (letter by G. Müller from Hamburg ends

up with "Heil Hitler"). When the correspondence is compared for

example with the documentation of a dispute between Kostrzewski

and bishop Antoni Laubitz concerning the architectural excavation

in Gniezno, which is full of emotions, then the "German mail"

is an unattainable model of fruitful negotiations filled with

respect. Analogically, in the majority of scientific publications

by both Kostrzewski and his students there are no political allusions,

or they are hid in statements relating to borders of Poland (Kostrzewski

1970, p. 130). |

| 2.2.2. Slavs vs. Germans - ideological fight |

The

disputes look differently when we look into the journalistic activity

of Kostrzewski or into his petitions for subsidies addressed to

authorities. Here the polemics with Germans, perceived as "refuting

unjustified German claims", was carried out in a similar method

and style as by German researchers (Kostrzewski 1970, p. 121).

He went into polemics with German archaeologists explaining some |

fig. 5 |

evident examples of nonsense

included in papers by e.g. Franz v. Wendrin who wrote about Germans

living in the Tertiary period, German king, Thorson who allegedly

had founded all cities in Poland already 200 000 years ago or

about Christ, the German king, or Ernst Petersen ( fig.

5) who claimed the Lech tribe on Silesia in Medieval Times

(Kostrzewski 1970, pp. 121, 187). It is worth remembering that

Józef Kostrzewski conducted the policy of Greater Poland that

was barely supported by the state government - on the contrary

to his German colleagues who had the full support of their state

authorities. |

An

exemplary archaeological site, the research results of which were

abused, was Biskupin

( fig. 6). The site was discovered in 1933

by Walenty Schweitzer and then researched for many years under

Kostrzewski's supervision ( fig. 7). The

research was accompanied by propaganda, but as it seems now the

Biskupin propaganda was mostly about advertising the archaeology

in order to receive funds for further research and to show archaeology

as a serious discipline of science that is worth

of such support (fig. 8,

9). Moreover the promotion

of |

fig. 6 |

fig. 7 |

Biskupin together with an appropriate national

propaganda (identifying the Lusatian culture with ethnos - the

Slavic ancestors) met the social demand and efficiently popularized

the archaeology as a scientific discipline and this was what the

Polish archaeologists needed at that time. Archaeology gave Greater

Poles, tired with the over-hundred fighting against Germanization,

a feeling of stability - we have been here for ages; not only

for the last one and a half thousands years, but "for ever". In

exchange for the subsidies the authorities expected some "practical"

results, so when Kostrzewski filed with the National Culture Fund

for a subsidy for works in Biskupin, he supported his request

as "refuting the unjustified claims of the German scientists concerning

the ethnographical relations in prehistoric Poland on the basis

of which The German scientists attempted to question Greater Poland

belonging to the Polish state" (UAM A-969). |

fig. 8 |

fig. 9 |

| 3.1. Science as politicians' servant |

In

1939 Germany attacked Poland and thus began World War II. In result

of some military activity Greater Poland was annexed to Germany

as Warthegau, although the borders between the Old and New Germany.

Scientific and cultural institutions were taken over by German

authorities that staffed them with Germans. Poles could work in

them only at the lowest posts - as cleaning persons, janitors

or drivers. The Wielkopolskie Museum regained its original name:

Kaiser Friedrich Museum.

The occupation of Poland

by the German army closed a particular stage in the history of

Germany. The German society frustrated with losing WWI and many

territories as the result of the war, and also with the later

economical crisis, began in the thirties to listen to nationalistic

slogans with attention greater than whenever and wherever before.

According to Adolf Hitler, Slavs as the "inferior people" on the

territory of Germany may at best serve the other and outside they

were allowed to manage by themselves, provided they recognize

the German superiority.

When founding the grounds

for their ideology, national socialists also took it down to prehistoric

times. Already on May 9, 1933 the interior minister, dr. Trick

stated that "the prehistory plays a prime role in teaching, as

it takes the beginnings of the Central-European cradle of the

German nation back in time; it is a superbly national discipline

of science" (Kostrzewski 1934, pp. 57-60). And this is how the

archaeology was boiled down to proving "scientifically" the superiority

of the "German race" over other races. The strong political stream

present in the German archaeology already from the 19th century

fostered the popularization of the national socialism among archaeologists,

all the more because after Hitler came to power, he offered jobs

to all unemployed prehistorians, provided they joined NSDAP, SS

or at least Deutsche Arbeitsfront. In the Scientific archive MAP

a prewar film commentary can be found reading, "inequality of

human races is an order intended by the God. As the contemporary

society aims at selecting the races, there is an obligation to

examine which anthropological and psychological features characterize

the German race. (

) The Northern races left some unforgettable

traces of their high culture, language, management abilities,

political and leadership talents". (

) Settled at first by Germans

(Goths, Burgunds and Vandals), lands in the east were left by

these tribes in the period of migration movements. (

) After the

Slavs entered the abandoned lands, Germans were trying to make

up the losses for many centuries." Completion of this historical

mission fell to the lot of the national socialists (MAP A-dz-52/5).

Before the outbreak

of the war, archaeologists were prepared for plundering any cultural

goods on the territories intended for conquering, and for an ideological

war. SS supervised all the activities by means of organizing special

excavation divisions and units designated for looting architectural

monuments on the conquered lands, and many others. An institution

called Ahnenerbe RFSS directed by A. Rosenberg played a vital

role. It organized offices that were responsible for taking the

possession of cultural goods on conquered territories for the

benefit of the Reich and for steering the cultural politics and

managing various cultural institutions. Each time Germans invaded

a country, in the second front line there were SS divisions specializing

in confiscating any historical objects and other valuable items,

accompanied by workers of the Trust Office assigned to administer

the conquered territory. |

| 3.2. Wielkopolska under the Nazi Occupation |

It

was not much different in case of Poland. In Poznań the German

Landeshauptmann took over the Prehistoric Division of the Wielkopolskie

Museum, renamed to Kaiser Friedrich Museum. Its Polish employers

lost their jobs or decided to leave them out of caution. Taken

over were also all buildings of the university. In the end of

1939 professor Hans Schleiff came to Poznań who was appointed

Der Generaltreuhändler für die Sicherstellung deutschen Kulturgutes

in den ehemals polnischen Gebieten, Treuhandstelle Posen (the

main administrator for matters related to securing German cultural

goods on the former territory of Poland; administrative center

in Poznań). He drew up a project for planned plundering of cultural

goods and for introducing new structures to museum management

and historical sites and objects protection. In keeping with the

project's guidelines in 1940 the Prehistoric Department was turned

into an office. It was called Landesamt für Vorgeschichte (LfV)

and carried out conservatory services and excavation works. It

supervised its affiliates among others in Łódź and Kalisz. The

office's main assignment for the years to come was to "Germanize

the collections" which should be understood as organizing them

according to some applicable German regulations. The post of the

Monuments Conservator was appointed, and when in 1941 the Reichsuniversität

was founded, Professor Ernst Petersen ( fig.

5) directed the prehistoric department.

In 1940 Freiherr Wolf

von Seefeld ( fig. 10) was employed in

the LfV. On November 5, 1940 Walter Kersten ( fig.

11), "an old comrade" who took care of Rhineland, Saxony and

Greece, became the director of LfV, which was strictly dependent

on the authorities of Warthegau. Among other archaeologists employed

in LfV worth mentioning were Günter Thärigen and Elisabeth Schlicht,

and an excavation technician Gustav Mazanetz. Some Poles were

employed there as well, including a few persons from Józef Kostrzewski's

staff - Władysław Maciejewski and Aleksander Waligórski. |

fig. 10 |

fig. 11 |

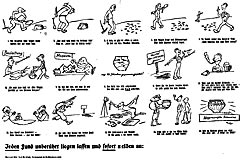

For

all German employees lesson of the Polish language were organized;

there are still class works available with propaganda texts for

translation (MAP A-dz-62/12). Due to the obligation to systematize

the materials no archeological research was planned other than

intervention works. The settlement of Biskupin was an exception

from this rule, the research of which was lead by an SS excavation

unit. A yearbook Posener Jahrbuch für Vorgeschichte was

founded, discoveries were exchanged so that they were stored at

the site of the discovery, and centralization of monuments and

books' collections was continued by means of plundering

the Polish resources. Al l documents,

the yearbook and press |

releases are simply full of propaganda

( fig. 12). The activity included: contacting

schools and organizations, guiding around the exhibitions, delivering

speeches and lectures, publishing results of archeological excavation

and intervention works in press. When in 1942 a reference book

on Poznań was released (Klock 1942, p. 5), the city was described

as the "uralten deutschen Vorburg im Osten" (ancient German

burg in the east). |

fig. 12 |

Another

assignment not related to a scientific research was an obligation

to write memoirs from war. The LfV workers who fought in the front

took down their experiences so they could be published in a special

"book of heroes". As the war extended in time and became truly

cruel, more "heroes" (MAP A-dz-47/5) had a chance to draft their

own picturesque stories. Memories of soldiers, full of vivid descriptions

of lice, ulcers, diseases, mud, vodka, museum, monuments and never-ending

victories were a source of admiration of men and women left at

the museum.

Another institution

that dealt with archaeology during the WWII was the Institut für

Vorgeschichte (opened on April 24, 1941). Professor Ernst Petersen

( fig. 5) was the manager, but his presence

there was only occasional as he occupied himself mainly with training

of the SS front divisions. A substitute teacher, Professor M.

Jahn from Wrocław, delivered lectures in the Institute instead.

After the death of Petersen in March 1944 Jahn became the head

of the prehistoric department. The Institute was busy finding

evidence of the "German nature" of Greater Poland, which can be

supported by some exemplary titles of lectures: Introduction

to early days of Warthegau, Migration of people and Vikings on

the territories to the east from the Elbe river, The culture of

facial urns and the Lusatian culture; the urns' holders fighting

for the German east. During a few operational years of the

Institute a dozen or so students learned there and in general

the Institute did not play any significant roles.

The German archaeologists

working in the war-time Poznań were mainly ardent advocates of

national socialism (surely with the exception of T. E. Haevernick).

In his letter to Kurt Langenheim, Walter Kersten ( fig.

11) expressed a belief that in Warthegau the Polish language

and Poles are doomed to extinction. Extermination or resettling

of Poles, although unpleasant, was entirely justified. Considering

himself a humanist, Kersten was prone to reach a compromise on

the territory of General Gubernia where only the intelligence

was to be exterminated and the living standard of poorly educated

people elevated so that they could be won for the national socialism

(MAP A-dz- 52/4). Kersten's remarks clearly show what the humanism

was about in the national-socialist version.

Until the beginning

of 1943 the archaeologists' enthusiasm relating to military victories

remained immense. "I was in Słupca

We are going to celebrate

the peace there (I hope)" - (MAP-A-dz-47/5) this is how on August

31, 1942 Kersten made an appointment with W. von Seefeld, at that

time in the front (Kersten died on April 7, 1944 south of Psków:

MAP-A-dz-47/1). In 1944 in the Poznań LfV there were only women

and Poles left, and the employees received no leaves and participated

in self-defense, sanitary, fire-protection and many other courses.

The affiliates in Łódź and Kalisz were closed, but the intervention

works were still carried out. In the end of 1944 some LfV workers

attempted to leave Poznań and head for the west (MAP A-dz-49/3),

majority however evacuated with other officials in the beginning

of 1945. Already in mid-December 1944 the premises of LfV were

taken over by uniform service Waffen SS and the soldiers staying

there ended up destroying partly the buildings and collections

(Kostrzewski 1970, pp. 249-250). |

| 4. The decay of World War Two |

The

war was finally finished but the consequences were disastrous

not only for German archaeologists, but mainly for Polish ones.

Gone were the followers of Józef Kostrzewski: Jacek Delekta (died

in Oświęcim), Zdzisław Durczewski (murdered in Warsaw), and his

students: Szubert (killed in 1939), Wydra (killed in the Warsaw

Uprising), Łukasiewicz (died in Oświęcim) and others including

one of Kostrzewski's sons. When all Polish archaeologists are

counted that were professionally active in the prewar period,

one fourth of them did not survive the war (11 persons); the next

7 did not return to the country.

In order to defeat Hitler,

the anti-Hitler coalition was forced to enter into an alliance

with Stalin. In 1944 it was clearly visible that it was mainly

Stalin who would decide about the future of the Central and Eastern

Europe. Due to Stalin's intervention Poland as the only state

of the anti-Hitler coalition lost a considerable part of land

in the East. In the end on the Jalta and Potsdam Conferences it

was determined that the loss would be compensated with some territory

along the Oder and the Lusatian Nysa including Szczecin and with

a part of Eastern Prussia. Nevertheless the territory of Poland

was decreased and it by as much as one fourth. Pursuant to the

decision by the anti-Hitler coalition Germans were resettled from

the territories awarded to Poland and from Sudety Mountains within

the borders of Czecho-Slovakia. Poles from the Eastern parts of

the country taken from Poland could leave for Poland and then

they were settled on the newly annexed lands in the West and North.

For many years to follow, the re-settlers lived with a conviction

of a personal injustice. Many Germans demanded a few times the

borders to be revised - and this according to the state of year

1937. |

| 5. The activity of Polish researchers |

| 5.1. The Institute for Western Affairs |

Already

in 1944, being aware of the planned territorial changes, a group

of Polish scientists coming from different regions (including

Greater Poland) who stayed in Kraków under compulsion specified

a goal for themselves. They wanted to prepare a scientific background

for these changes and to make the Polish citizens aware of their

rights to these territories. In December 1944 historians: Zygmunt

Wojciechowski, Maria Kiełczewska and Jan Zdzitowiecki founded

the Institute for Western Affairs, which was a research and development

station focused on the entire aspect of Polish-German relations.

Following the liberation, Poznań was supposed to be its place

of residence as the most natural environment due to its traditions

and geographical location (Bilans I roku

1946, pp. 291-295, Z

życia IZ 1947, pp. 362-376, Pollak 1955, pp. 469-472). Having

received the Prime Minister's approval in February 1945, the Institute

started its legitimate operation (Bilans I roku

1946, pp. 291-295).

Its charter read: "The aim of the Institute is to examine the

integral relations between Slavic countries, and particularly

Poland, with Germany; their course, lands that constitute their

territories and peoples living there". The Institute aimed at

providing Polish schools and society with necessary material -

decent and honest information about the Polish origins of recently

recovered lands (Bilans I roku

1946, pp. 291-295). In its first

years the Institute incorporated also the archaeologists. On May

12-18, 1947 in Osieczna an informative course on the Recovered

Lands took place for educational workers from the Western and

Northern Poland. W. Hensel delivered a speech there (Z życia IZ

1947, p. 586) on the ancient times of the lands. Generally, all

the numerous papers published by the Institute for Western Affairs

were to make Poles more familiar with the Recovered Lands, which

was the case with a linguistic paper by Lehr-Spławiński "About

the origins and prehistoric father land of Slavs" (Bilans I roku

1946, pp. 291-295) or a paper by Kostrzewski "Pre-Polish culture". |

The

Institute for Western Affairs was not the only institution concerned

with integrating the western lands with the rest of Poland. Having

returned to Poznań already on March 3, 1945 (Kostrzewski 1970,

pp. 245-246), Kostrzewski immediately got down to reconstructing

the Poznań archaeology. At first he occupied himself with renovating

the building of the museum and with recovering various collections

taken away to towns around Greater Poland but also to a salt mine

in Grassleben in Brunswick. On the other hand being almost entirely

destructed, the University Institute of Prehistory had to start

from the beginning. Kostrzewski developed a vivid style of work,

focusing on three main tasks: reconstruction of archeological

institutions, obligations of a conservator, and participation

in site planning of the Recovered Lands. The Museum remained independent

- it was now called Prehistoric. The museum building became home

also to two university departments: the Institute of Prehistory

and the Institute for Slav Antiquity Research in operation between

1945 and 1950. The later took over the excavation works in Biskupin.

In 1945 the Polish Prehistoric Society was reactivated.

Having assumed that

all archeological monuments are "ours" irrespective of the nationality,

which was a type of thinking characteristic to the Poznań archaeologists

already in the 19th century, in the first postwar years Józef

Kostrzewski took under his conservator's wings the territory of

the then Poznań province which covered areas up to the Oder and

the West Pomerania. He was mostly interested in "rubbled museums"

and mansions left behind by Germans that were constantly robbed.

And so he took all that to Poznań, declaring a return as soon

as new, appropriately staffed museums are founded in Pomerania

(MAP A-dz-80/3). Naturally it was only possible for a small part

of all collections - Stafiński, a coworker of Kostrzewski, estimated

that 70% of regional museums collections were stolen or destroyed

by newcomers (MAP A-dz-80/3).

The third field of Professor's

activity covered his participation in the cultural planning for

the "Recovered Lands". Apart from the salvation action, the director

of the Prehistoric Museum launched a popularization program on

prehistoric times of Greater Poland and the Recovered Lands. His

first lecture on the archaeology of Pomerania (PAN A-JK-106) he

delivered already in April 1945. Next lectures followed and the

Prehistoric Museum organized temporary exhibitions on prehistoric

times of Lubuskie Land (MAP A-dz-80/2). In 1945 the castle in

Poznań presented archaeology on an exhibition organized by the

Polish Western Society, Poznań District, which was devoted to

the fight against the German rule and which showed the Western

Lands (MAP A-dz-82/1). On the turn of February 1946 the Wielkopolskie

Museum organized a series of lectures on prehistoric times of

Slavic nations and Poland (MAP A-dz-80/1). Moreover, cooperation

developed with such institutions and organizations as provincial

governments, forest inspectorates, local units of information

and propaganda and the Monuments Protection Department. In 1946

Professor Kostrzewski cooperated with the Editors of the Polish

Atlas residing at the Measurements Main Office. The Editors were

preparing the so-called small atlas in relation to the Peace Conference

(MAP A-dz-82/3).

Naturally, as years

passed by, the stress put on fighting against Germans became weaker

and the celebrations related to 1000 years of the Polish state

became more significant (the anniversary was in 1966). Poland

fell within the reach of the Soviet Union's policy, which for

humanities meant nothing else but introducing Marxism as the methodological

basis. On no account was Kostrzewski able to popularize Marxism,

so in spite of the entire recognition the authorities had for

his Pre-Slavic theory, he was made to retire from the university

but remained the director of the Museum. In reaction to attempts

to centralize the archaeology and to transferring the control

center to Warsaw as well as establishing the German Democratic

Republic, the Poznań-German polemics became weaker and when they

happened, they were always approved by Warsaw. Therefore as it

seems to the authors of this paper, the main stream of Poznań

habitants fighting for the western lands ended rather in the beginning

of the 1950s and not in 1956. |

When

in polemics with German archaeologists, Józef Kostrzewski applied

a similar style and the same ethnographical method, but the sense

was different.

Kossina dared to use

such statements as: "For Germans, who always, and even more in

a time of war, have a strong desire of law and order, they [Slavs]

were just objects of abhorrence and atrocity" (Kostrzewski 1970,

pp. 154-155). At the same time Kostrzewski would compare migration

of Germans to the movement of Gypsies (Kostrzewski 1970, p. 155)

- a comparison seemed offensive to Germans but only because of

their belief in the race theories fashionable at that time. Professor

also reminded that although there is a German minority in Poznań,

it does not signify that it is a German country, to the same extent

as the German Westfalia cannot be Polish only because a quarter

of a million of Poles live there (Kostrzewski 1970, p. 113).

Both Poles and Germans

were legitimate to express their opinion on lands with mixed ethnic

origins such as Silesia or Pomerania. No wonder both sides reached

to historical arguments, however those were possible to prove

only as far in the past as by medieval times. When research is

made deeper in time, where reconstruction of the past is only

hypothetical, conclusions are already abusing the rules of science.

When a side to a dispute presents racial arguments to support

extermination of a particular group of people, we can call it

a crime.

In case of Kostrzewski

we talk about using the hypothesis about the Preslavic origins

of the Lusatian culture to support the rights to land, and this

only in journalistic and not strictly scientific texts. The style

of his argumentation was strongly influenced by his explosive

temper, which resulted in numerous arbitration commissions and

court cases where he was either the insulting or the insulted

party. The main goal of the Polish-German polemics was to prove

the rights to the disputable lands that "always were and will

be ours". Kostrzewski had an easier task here as without any trouble

he could show that Poles and not Germans were first to live on

the territory of both Silesia and Pomerania. In the end it was

the politics and not history that decided about the shape of borders

of our countries.

In one more thing Germans

and Poles could not agree. When the German scientists put forward

a hypothesis about historical rights of Germans to Greater Poland,

after a few dozens of years all graduates from German elementary

schools in the Poznań province knew that they live on the piece

of land that historically could belong to them. After the war

attempts were made to teach some prehistory in Polish schools,

but not for too long. Connections between Poland and the Recovered

Lands were convincing only to those settlers who came from Greater

Poland. For families coming from the east the Masurians and Silesians

who spoke a dialect filled with German vocabulary were the "natives",

understood as Germans, a strange element. Misunderstandings between

the two groups lead to emigration of many natives.

Recently the concept

of Pre-Slavic origins developed by Józef Kostrzewski is being

criticized ever stronger, particularly by the Polish archaeologists

majoring in the period of Roman influences. However, the opponents

have not developed their own research method but returned to the

classic methods of Gustav Kossinna, also in terms of the style

of vivid polemics with skeptics who doubt in the possibility to

specify the ethnos of the archeological culture exclusively on

the basis of discovered objects. And so the mystery of the Slavs'

origin is still waiting for new concepts. |

Bilans I roku

1946 Bilans I roku pracy Instytutu Zachodniego. Sprawozdanie dyrekcji złożone na walnym zebraniu członków w dniu 16 marca br., Przegląd Zachodni, t. I, s. 291-298

Jakóbczyk W. (red.)

1998 Dzieje Poznania: lata 1793 - 1918, t. 2, cz. 2, Warszawa

Grześ, B., Kozłowski, J., Kramski, A.

1976 Niemcy w Poznańskiem wobec polityki germanizacyjnej 1815-1920, Poznań

Kaczmarek, J.

1996 Organizacja badań i ochrony zabytków archeologicznych w Poznaniu (1720-1958), Poznań

Klock, E.

1942 Posen, Chronik der Gauhaupstadt Posen, Posen

Kostrzewski, J.

1914 Wielkopolska w czasach przedhistorycznych, Poznań

1919 Die ostgermanische Kultur der Spätlatenezeit, Mannus Bibliothek

nr 18 i 19,

Lepipzig, Würzburg

b.r.w. (po 1930) Początki kultury ludzkiej, Poznań

1930 Vorgeschichtsforschung und Politik. Eine Antwort auf die

Flugschrift von Dr.Bolko

Frh. von Richthofen: Gehört Ostdeutschland zur Urheimat der Polen,

[Poznań?]

1934 Historiografia hitlerowska a prehistoryczna teoria Kossiny,

Z Otchłani Wieków,

R. IX, s. 57-62

1946 Gospodarka niemiecka w Poznańskim Muzeum Prehistorycznym,

Z Otchłani

Wieków, R. XV, s. 4-9

1970 Z mego życia, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków

Nowa

1996 Nowa Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN, t. 4, Warszawa

Piotrowska, D.

1997-1998 Biskupin 1933-1996: archaeology, politics and nationalism,

Archaeologia

Polona, vol. 35-36, s. 255-285

Pollak, M.

1955 Instytut Zachodni. Powstanie i rozwój organizacyjny,

Przegląd Zachodni, R. XI,

t. 1, s. 469-486

Rączkowski, W.

2003 Expansion and reaction: The concept of Polish Archaeology

in the discourse

with German archaeologists (referat wygłoszony na konferencji

Area_III:

"Archaeology, expansion, resistance"), Poznań, 12 czerwiec 2003

r.

Rohrer, W.

2003 Archäologie und Propaganda. Die Ur- und Frühgeschichte von

1918 bis 1933.

Bespiel Schlesien, Berlin, (maszynopis pracy magisterskiej)

2003 Science between propaganda and polemics archaeology in Upper

Silesia 1918

to 1933 (referat przygotowany do publikacji w czasopiśmie Archaeologia

Polona)

Tacyt,

1957 De origine et situ Germanorum [w:] Dzieła, t. II, Warszawar

Z życia IZ

1947 Z życia Instytutu Zachodniego, Przegląd Zachodni, t. I, II s. 360-377, 586-588

|

| Consecutive numbers of the documents used in paper: |

|