|

Jarmila Kaczmarek

(Poznań Archaeological Museum)

Megalomania and expansionism.

On Polish-German relations within archaeology

in the Wielkopolska region

|

During

the past few years, the supporters of Slavic allochtonism theory

have been discussing with the followers of Slavic autochtonism.

The allochtonists claim that Józef Kostrzewski developed the theory

of Slavic neoautochtonism east of the Odra River in order to balance

German autochtonism, the theory developed by Gustav Kossina. Józef

Kostrzewski, Kossina's disciple, based his ideas on political

reasons and on "sheer spite" - in order to oppose German expansionism

by means of the Polish one. This conviction seems to be popular

among archeologists from the former Russian and Austrian partition

of Poland, for whom the experiences of the inhabitants of the

former Prussian partition seem quite incomprehensible.

Before I present Poznań

records and rare publications which constitute the source for

this presentation, I wish to recall the definition of expansionism.

This term covers the intention of a state to expand its territory.

When a conflict relates to a part of a given country, we can only

talk about national, religious and social conflicts based on i.e

unequal treatment of a group of citizens by the government, nationalism

or megalomania.

Mieszko, a Polan prince

of Wielkopolska received baptism in 966 AD, thus introducing his

country to the culture of Christianity and, via west European

clergymen of Latin order, his territory was accepted on the arena

of west European culture and antique traditions. As early as in

the 13th century, a Polish bishop from Krakow, Wincenty Kadłubek,

in his "Chronicles of Poland" tried to combine the history of

Poland with ancient history which was so close to his heart. According

to him, Gaelic Lechistan people, who fought successful battles

against the army of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, were

the ancestors of contemporary Poles. Kadłubek axiomatically assumed

that Poles settled on the territory marked by the Vistula and

Odra Rivers and the Baltic Sea several hundred years BC at least.

This "Gaelic link" made it very clear that Kadłubek was convinced

of the autochtonism of ancient Poles, even though they seemed

to be present in source materials under a different name. This

direction determined by Kadłubek was later followed by numerous

authors.

After 1450, an imperial

position of Poland among other European countries needed to be

further supported. Therefore, the antiquity of Poland and its

centuries-old independence had to be proved. Hence the attempt

to identify Poland with European Sarmatia, the state which extended

all the way to the Rhine and related to the Teutonic tribe. The

other member nation of the Republic of Poland, the Lithuanians,

were to originate from ancient Rome. The Sarmatian myth was so

common among the Polish noblemen that their culture between the

16th and 17th centuries was later called

a Sarmatian one. As the knowledge of Latin increased, the Bible

and antique literature, including "Geography"

by Ptolemeus, |

fig. 1 |

became very popular.

In the 16th century, Poznań was identified with

the ancient Stragona, mentioned by Ptolemeus (Sarnicki 1587).

Combined with megalomania such interpretation could have ended

with the grotesque, as in Wojciech Dębołecki's book (published

in Warsaw in 1633), when author tried to prove that the Slavic

(identified with Scythian) were the oldest nation in the world,

while biblical Adam and Eve, in paradise,

|

spoke Polish ( fig. 1).

Also in Germany, the

history of the state had been glorified since 15 th century, yet

its history was derived not so much from the Antiquity but from

the Middle Ages. For instance, a renowned historian of that time,

Heinrich Bebel, put emperors from Otto dynasty much higher in

hierarchy than pagan Greeks and Romans. Johannes Nauclerus who

lived in the 16 th century believed that Providence itself gave

the Germans power over the world, and that the Germanic tribe

was the oldest nation in the world. It was in Germany, in the

beginning of the 16 th century, that fir the first time the issue

of the right to a previously occupied territory was raised. At

that time, the issue pertained to German - French dispute over

Alsatia. A historian of that time, Jacob Wimpfeling claimed that

the French did not have a historically justified right to that

region. A hundred years later a similar question was raised with

regard to the precedence of settlement in Lusatia, where the issue

of co-existence of Slavic and Germanic tribes was discussed. Even

as late as the year 1783, a German historian Karl B. Anton advocated

the primate of Slavs with this respect. Soon enough all this was

to change.

In 18 th century

Poland, in the Enlightenment the ethnogenesis of Poles was a subject

of great interest. The theory of conquest was at that time the

most popular one. Historians looked for the cradle of Slavs in

the east (e.g. in Kolchida or on the Dnieper, the Volga or the

Don) or in the south, in Croatia, Slovakia, Iliria). The ancestors

of Poles were to conquest in the 6 th century AD the

original inhabitants of later Slavic territories. Various theories

concerning ethnogenesis uplifted the readers and were used to

manipulate the citizens at the times of feuds between social classes,

as well as to justify the political system. They were not used,

however, for territorial claims. The Republic of Poland itself

was a multi-ethnical and multi-religious state. The co-existence

of so many nationalities was never a bed of roses, yet conflicts

were not present between minorities but between social classes.

The theory of conquest was used as well (it was generally believed

that the noblemen were Lechistanian and the peasantry were Sarmatian). |

At

the end of the 18 th century, Poland was partitioned by Russia,

Austria and Prussia. If one can believe Józef Kostrzewski, Frederic

the Great, asked for an justification of his occupation of another

country's territory, replied that his historians would somehow

think of the right excuse. The Germans perceived Polish noblemen

proudly dressed in oriental robes, having a different culture

and values, in the same way as the 19 th century Europeans perceived

savage Bushmen ( fig. 2). It was

clear for them that real culture was

the one |

fig. 2 |

of German language and tradition, therefore they expected

a blitz assimilation of their new citizens into German culture.

Only when it was clear to the Germans, that the majority of Polish

people do not even think to "civilize", did they begin to gradually

adjust legal regulations in order to enforce the "civilization"

on the oppressed Polish nation.

Johann Droysen was a

19th century German supporter of the theory of mixing politics

and history. Soon enough he found numerous followers. In the newly

formed science of races, or rather of language groups, the Indo-European

group was shortly defined as the Indo-Germanic one. The name supposed

to be right because in the Middle Ages Germanic tribes influenced

Indo-European civilization so much, that in the areas where their

influence was weaker, until now civilization is not "pure European".

This opinion was popularized, also among some Poles, but later

the terminology was substituted with Aryan terms. The adjective

"Germanic" really meant "German", which was particularly stressed

in the areas where Germany had its territorial interests. |

fig. 3 |

Polish

people were not at all delighted to be ruled by the new government,

which was generally perceived as the oppressors. Many illustrations

of the mentality of that time can be found in the contemporary

newspapers, for example in case of Polish farmer accused of killing

German surveyor. Although he did not deny, the court found him

not guilty, as he explained that he was sure he met the Evil One.

Since on contemporary iconography devil |

was presented in a German dress ( fig.

3), one cannot be punished for killing fiend! In the 19 th,

as the national awareness grew within social circles, it was not

politically correct to give to the Germans Polish national relics

of the past (including archaeological collections). It was not

in good taste to socialize with the oppressors, what in turn brought

about polonization of some German families, especially those living

exclusively among Poles.

Political situation

of those times and the establishment of modern history and archeology

favored the creation of Polish archeological collections, what

was then considered to be a patriotic duty revealing itself by

protecting relics from long gone past. A vast majority of the

19 th century documents, being in possession of Poznań Archaeological

Museum archives, bears traces of this patriotism. Archeological

artefacts, although at that time it was not possible to date them

properly, were collected just for the patriotic reasons. The origins

of nations were examined. As early as in 1857 Wojciech Konewka,

a Polish inhabitant of the island of Ruegen, wrote: "There are

different opinions on the residence of Slavs in this area. Some

say that Slavs were present on these abandoned countries already

in the 5 th century, others believe that Slavs have always been

here." One of the most prominent historians of the 19 th century,

Joachim Lelewel, advocated autochtonism of Slavs and their origin

from (related to Tracks) the Getts and Dacs. He was of an opinion

that such a great nation could not have just arrived from nowhere,

but it had to form in the area, so the ancestors of Slavs must

have settled on the Baltic Sea and the Vistula soon after the

Flood. The tradition of reaching for antique sources and the attempts

to identify Slavs with tribes mentioned by ancient authors was

widespread. The book written by a Slovak historian, P.K. Szafarzyk,

translated into Polish in 1842, was widely respected in Poland.

The author, referring to Jordanes, considered all Weneta tribes,

also the ones living on the Adriatic, with Slavs. He even assumed

that a part of Tracs and Ilirians could have been Salvs as well.

As for the times of Slavic arrival on the banks of Vistula River,

F. Duchiński, a 19 th century historian assumed the year 1000 BC.

There were authors who dated this fact even later in history.

Under the theory of the long-distance ancient trade, numerous

Phoenician factories were considered as "Slavic". Moreover, also

Etruscan, Greek, Roman and other colonies were considered as Slavic.

Shortly before World War One, a Czech researcher, J.L. Pič, opted

for Slavic origins of Lusatian culture, yet he was unable to support

his theory with any evidence. It should be noted here, that already

in 19 th century uneducated villagers called cremation cemeteries

as Aryan, megaliths and grave-mounds as the burials of Huns or

giants and Medieval strongholds as Swedish trenches. All in all,

in the course of the 19th century numerous theories and concepts

on the origin of Slavs and Germanic tribes were created.

Originally, those theories

were not used to justify the rights to land, with maybe one exception

of Pastor Karl Wunster who claimed in 1824, that the traces of

the Germanic tribes in Wielkopolska could be found. Even in 1830,

artefacts from Wielkopolska shown in Berlin were defined as "the

collection of Slavic relics", without the chronological diversification.

Prussian governments tried to use numerous decrees concerning

the protection of the relic of the past in order to create the

collection in Berlin museums. In 1862, a Cracovian art historian,

Józef Łepkowski, complained that "when only a German researcher

finds an ornamented funeral relic in the ground, (...) he immediately

decides of its historical value and unmistakably ascribes

it to Germanic past". Due to

the respect for science |

shared by many,

the 19 th century Polish and German scientists declared

that science was international in its nature and could not be

used as a tool to defend interests of any nation. This cliché

was usually followed by "but" which introduced the denial of the

former manifesto ( fig. 4).

After the successful |

fig. 4 |

war of the Germans against the French in

1870s, the historical awareness was purposely and systematically

used to fight for territory, which brought about the increased

German nationalism. If one may believe the publications of that

time, the PTPN presentation of Wielkopolska relics at the exhibition

in Berlin and Wrocław in 1880s showed that the artefacts of Lusatian

culture were almost identical on both banks of the Odra River.

Soon after that a hypothesis emerged that Germanic settlement,

preceded the Slavic one. Germanic tribes were obviously identical

with the Germans of that times, thus the right of the Germans

to own Wielkopolska were |

fig. 5 |

undeniable ( fig.

5). It was believed that the general public was not at all

indifferent to the question whether the nation derives from Asia,

or if it is autochthon on the land it owns. Originally a very

simple division was applied - Germanic relics were the ones of

great artistic value, Slavic ones were the primitive and not ornamented

ones. In this way, even Wilhelm Schwartz, a renowned in Wielkopolska

historian of Antiquity, who co-operated

with |

his Polish colleagues, having found in 1879

the graves from the times of Lusatian and Pomeranian cultures

in the vicinity of Poznań described them as Slavic due to "a simple

pottery technique and a lack of ornaments". When it became evident

that it was hard to differentiate archeological material according

to this concept, the Germans developed a new methodology hoping

that maybe minute details would be useful to prove the Germanic

origin of the items. A society called Historische Gesellschaft

f. die Provinz Posen was organized "to present and shed proper

light on the participation of the Germanic culture in the development

of the Poznań region. (

) That would lead to creation of workpiece

deserving the influence exerted by Germanic culture during the

course of all time on the development of the Eastern Margraviate

of the German State" ( fig. 6). Gradually,

a thesis was accepted that the occupation of Wielkopolska by Prussia

was really its return to the mother country and that the new settlers

had all the reasons to feel at home in the occupied land. The

Pomeranian culture was Germanized, while the Lusatian culture

was defined as "Trackian" ( fig. 7) or

"Ilirian". By summoning to collect historical relics, the patriotic

dimension of this activity was strongly stressed. "Historische

Geselschaft" ( fig. 8) reads: "The authorities

strongly support The Museum (...), because of its deeply patriotic

and scientific aims". The conviction of the Germanic supremacy

over the Slavs was fully reflected in the views of Gustav Kossina,

who claimed that" Slavs have always admired bolshevism of some

sort, which was only less severe by impossibility to gather and

by an utter lack of needs. The Germans, who have always, particularly

at the times of wars, been enlivened by the need of law and order,

detested and despised the Slavs." |

fig. 6 |

fig. 7 |

fig. 8 |

Those

views evoked a defensive reaction, which was not always very conscious.

In response to them, Polish historians wrote publications that

pointed to a very high or exceptional level of Slavic or Polish

cultures, which were not always identical. For instance, Wiktor

Czarnecki in his book published in 1900 wrote about the exceptional

role of Poles. In a letter to an unknown person, written in 1910

and attached to a copy of his book, he summarized his views as

follows: "in general, what I have written in "Scythia", is undoubtedly

true. We Poles, are not really Slavs, but belong to a much more

ancient culture, we are the pre-cultural or pre-civilization element

since we have been living in this pre-country of all human legends

for ages. Our language reverberates the echo of pre-civilization

and pre-culture. (...) Our language obviously belongs to the Slavonic

group, but the Slavs were an eastern tribe, which later flooded

us (...). Primarily between the Rhine and man-made embankments

in the east lived German families in the meaning legal since originated

from ritually contracted marriages (...). The people from Germany,

quite unrightfully usurped the name German, as their national

name, for in those distant times there had been no Germanic nation.

Tacit, who includes us within Germania is right, and he only points

at a pernicious influence of anti-cultural, nomadic, steppe Slavs,

flooding in from the east. (...). In Eddean Alwissmal is the key

to European languages which were formed at the time when the Polish

and German state were being established, both countries being

countries of the world, with no borders."

Prof. Jan Sas Zubrzycki,

an architect from Lvov was one of the supporters of Slavic supremacy

over other nations. According to him, the Slavs had used bricks

for constructing their homes even before Christianity was introduced

on the territory, and Slavic art was more valuable than the art

of any other nation. He called Celtic art "pre-Slavic" and he

believed that "Poland emerged from the Slavic nation which occupied

almost all of North-Eastern territory of Europe, even a part

of Italy, France, Spain and England." In 1921 he could still see

the connection between Slavic art with the art of Mykenes, Troy,

and the name of Tracks he derived from "tracze", which in old

Polish meant "carpenters". Germanic Wenedas mentioned by Ptolemy,

according to Zubrzycki, were to be Slavs living on the Rhine,

only this tribe was the first to be denationalized by Teutons.

In many other papers written in the turn of 19 th and

20 th centuries old ideas of Slavic Tracks, Getts and

other antique tribes were mentioned. Thus, as soon as Józef Kostrzewski,

familiar with the ideas of J. Pič and Szafarzyk, and also other

Polish authors, learned in Berlin that G. Kossinna had also claimed

Lusatian culture to be Ilirian and Trackian one, he immediately

combined both approaches, especially that at that time the state-of-the-art

scientific tools which he got to know in Berlin, seemed to enable

the confirmation of this idea. |

In

documents of Poznań Archaeological Museum from the inter-war period

there is no evidence of expansionism in archeology. This historical

period is further discussed in another presentation. The subject

had its very stormy come back in the years 1940 - 1944 when the

museum was in possession of the German Nazi. Pre-history became

a political science, and its sense was very well illustrated on

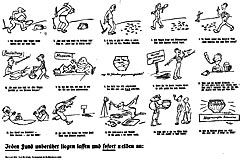

a poster published at that |

fig. 9 |

fig. 10 |

time ( fig.

9) which encouraged the protection of historical relics. Also

in their private correspondence, German archeologists supported

Hitler's politics of expansion, one exception being Ms. T. Haevernick.

There are letters which show that along with German successful

battles on the frontline, their historians tried to seek in the

East (Caucasus) first only Scythes, then they looked for the elements

of La-Tene culture there, and finally Indo-Germanic or Indo-European

ones which obviously had to originate from Caucasus ( fig.

10). The defeat of Nazi army put an end to this blooming imagination. |

To

sum up, nationalism, megalomania and expansionism in Polish and

German archeology happened, yet their intensity varied depending

on political situation. Most often they were a menace, still in

Poznań we may talk about one positive aspect of this expansionism:

subsequent Polish or German authorities of Poznań Archaeological

Museum did not destroy any documents found by their predecessors,

which was common in other institutions, since all of the source

materials were treated as "our national heritage", even though

the heritage was not definitely mutual. |

Bibliography

(unknown author)

1707 Stragona Abo Stołeczne Miasto Poznań oraz Tabula accuratissima

Tam per totam MaioremPoloniam quam Extra Regnum iak wiele Do Cudzoziemskich

Miast mil rachować się ma Wystawiona w Roku Pańskim 1707,

Poznań

(unknown author)

1839 Zbiór starożytności słowiańskich w Berlinie, Przyjaciel Ludu V/2, pp. 332-335

(unknown author)

1872 Miersuae Chronicon, Monumenta Poloniae Historica II

(unknown author)

1926 Kości Adama i Ewy, Dziennik Poznański z 17 VI 1926, p. 11

Anonim (so called) Gall,

1965 Kronika Polska (transl. R. Grodecki), Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków

Anton, K. B.

1783 Ueber der Alten Slawen Ursprung, Sitten u.s.w., Lipsk

Dębołęcki, W.

1633 Wywód jedynowłasnego państwa świata, w którym pokazuie

X. Woyciech Dębołecki z Konoiad, Doktor Teologiey S. a. General

Społeczności wyjupywania Więźniów, że nastarodawnieysze w Europie

Królestwo Polskie lubo Schythickie tylko na świecie, ma prawdziwe

Succesory Iedama, Setha, y Iapheta, w Panowaniu Światu od Boga

w Raiu postanowiony, Warszawa

Duchiński, F.

1901 Pisma Franciszka Duchińskiego, vol. I, Rapperswyl, (1st ed. 1858)

Endrulat, B.

1885 Über die Aufgaben der historischen Gesselschaft für die Provinz Posen, Zeitschrift für die Historische Provinzial Gesellschaft, Year I, pp. 5-13

Grabski, A. F.

2003 Dzieje historiografii, Poznań

Lelewel, J.

1853 Narody na ziemiach sławiańskich przed powstaniem Polski. Joachima Lelewela w dziejach narodowych polskich postrzeżenia. Tom do Polski wieków średnich wstępny, Poznań

1859 Dzieje Polski synowcom przez stryja potocznym sposobem opowiedziane, Poznań

Kaczmarek, J.

1996 Organizacja badań i ochrony zabytków archeologicznych w Poznaniu, Poznań

Kadłubek, W.

1974 Mistrza Wincentego Kronika Polska, Warszawa

Kostrzewski, J.

1970 Z mego życia. Pamiętnik. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków

Kokowski, A. (ed.)

2002 Cień Światowida, Lublin

Łepkowski, J.

1862 Z przeszłości. Szkice i obrazy. Artykuły felietonowe Józefa Łepkowskiego. Sztuka u Słowian, szczególnie w przedchrześcijańskiej Polsce i Litwie, Kraków

Malinowski, T.

2003 Cierń Światowita, Poznań-Zielona Góra

Neustupny, J., Pič J. L.

1947 Słowiański historyk i czeski prehistoryk, Z otchłani wieków, Year XVI, pp. 89-91

Prusisk, W.

1899 (app.), Scythia biformis, das Urreich der Asen. Eine Skizze aus der polnisch-deutschen Vorgeschichte, Breslau

Sadowski, J. N.

1877 Die Handelsstraßen der Griechen und Römer durch das Flußsgebiet der Oder, Weichsel, des Dniepr und Memel zur Ostsee, Jena

Sas Zubrzycki, J.

1914 Zwięzła historja sztuki, Kraków

Schwartz, W.

1879, Verhandlungen, Zeitschrift für Etnologie, pp. 376

Stryjkowski, M.

1846, Kronika Polska, Litewska, Żmudzka i wszystkiej Rusi

, Warszawa, p. 22 ( 1st ed. 1582)

Szafarzyk, P. J.

1842, Słowiańskie starożytnosci, Poznań

Archiwum Naukowe MAP, nr akt A-dz. 2/1

|

|